Offizieller Titel: The effect of large scale migrationand food source changes on the gastrointestinal microbiome of the lesser long-nosed bat (Leptonycteris yerbabuenae) and its implications of conserving a recently recovered species

Name des Forschers: Luis Roberto Viquez-Rodriguez

Projektlaufzeit: 01.03.2016 - 28.02.2017

In meiner Dissertation möchte ich herausfinden, wie ein saisonales Verhalten, wie die Wanderung zwischen zwei verschiedenen Ökosystemen (Trockenwald vs. Wüste) und die mit der deutlich unterschiedlichen Pflanzenverfügbarkeit verbundenen Änderungen in der Nahrung das Mikrobiom des Verdauungstraktes von Blumenfledermäusen beeinflusst. Hierzu vergleiche ich die migrierende Blumenfledermaus Leptonycteris yerbabuenae mit der nahe verwandten, aber nicht wandernden Glossophaga soricina, einer der häufigsten und am weitesten verbreiteten Blumenfledermaus des gesamten Neotropis.

1. Quantifizierung der Effekte von Migration und saisonaler Nahrungsänderung auf das gastrische Mikrobiom von Leptonycteris yerbabuenae

2. Vergleich der saisonalen Ausprägung des gastrischen Mikrobioms zwischen der migrierenden Blumenfledermaus Leptonycteris yerbabuenae und der stationären Glossophaga soricina.

Im Jahr 2016 führte ich in Mexico drei Feldexpeditionen durch. Die erste im April nach Callejones (Colima) und Chamela-Cuixmala (Jalisco); die zweite zum Vulkan Pinacate (Sonora) im Mai und die letzte nach Chamela Cuixmala von November-Dezember.

Hauptziel dieser Feldaufenthalte war es, Microbiom-, Pollen- und Gewebeproben für mein Projekt zu erhalten. Der Fangerfolg war zufriedenstellend, wenngleich etwas heterogen. In Callejones erhielten wir insgesamt 27 Proben von Leptonycteris yerbabuenae und Glossophaga soricina. Wir fingen die Fledermäuse in Bananenplantagen und entlang des Flusses Coahuayana, an der Grenze zwischen den Bundesstaaten Colima und Michoacán. Auf der Insel Don Panchito bei Chamela-Cuixmala konnte ich nur 9 Tiere fangen, da zu diesem Zeitpunkt lokal einige Unstimmigkeiten bezüglich der Eigentumsverhältnisse des Strandes bestanden, von dem wir mit dem Boot zur Insel starten konnten; wir mussten die Probenahme an dieser Stelle daher kurzfristig verschieben.

Die Exkursion zum Vulkan Pinacate in der Sonora Wüste war ein großer Erfolg und wir konnten Proben von mehr als 90 Tieren sammeln. Im Mai sind viele Leptonycteris - Weibchen entweder schwanger oder laktierend. Um mögliche Komplikationen zu vermeiden, arbeiteten wir daher nur mit nicht schwangeren Tieren. Dies war bereits das zweite Jahr der Probenahme am Pinacate und ich werde diese Untersuchungsstelle letztmalig im Mai 2017 besuchen.

Zwischen November-Dezember 2016 holten wir den aufgeschobenen Besuch an der Insel Don Panchito bei Chamela-Cuixmala nach. In 15 Nächten gelang es uns diesesmal erfreuliche 126 Tiere zu fangen und auch von allen Proben zu bekommen.

Seit dem Abschluß dieser Feldsaison arbeite ich im Labor an der Analyse meiner Proben. Im März begann die Analyse der Pollenproben zur Identifikation der Nahrungspflanzen und und seit April arbeite ich an der Aufbereitung der Microbiomproben.

Englisch Summary:

In my PhD – project I want to determine how a key life history factor such as the migration between two different ecosystems (coastal dry forests vs deserts) and the inherent diet shift due to the change in the floristic composition affect the intestinal microbiome of nectar-feeding bats. I will compare the migrating Leptonycteris yerbabuenae with the non-migrating Glossophaga soricina from the same subfamily, one of the most abundant and widely distributed nectar-feeding bat species in the entire Neotropics.

Research objectives:

1. Determine the effect of migration and cyclic diet changes on the gastrointestinal microbiome of Leptonycteris yerbabuenae

2. Compare the annual changes of the gastrointestinal microbiome between a migratory (Leptonycteris yerbabuenae) and a non-migratory nectar-feeding bat (Glossophaga soricina)

Over the last year I undertook three field expeditions in Mexico. The first one in April to Callejones (Colima) and Chamela-Cuixmala (Jalisco), the second to the Pinacate Volcano (Sonora) in May and the last again to Chamela Cuixmala in November-December.

Main goal of these expeditions was to get microbiome (fecal), pollen and tissue samples for my project. In Callejones, we collected samples from the Lesser Long-nosed bat (Leptonycteris yerbabuenae) and from Pallas’ Long-tongued bat (Glossophaga soricina). We captured bats within banana plantations and along the Coahuayana River on the border between the states of Colima and Michoacán and were able to catch a total 27 bats. In Chamela-Cuixmala, we were only able to capture 9 Lesser Long-nosed bats, before we had to postpone further field work. This was mainly due to local disagreements about land ownership of the beach from which we were supposed to sail from. These problems led to certain security concerns and we therefore had to suspend the sampling after only few days. During the remaining time of the visit, we explored the area for other possible roosts. We were able to rediscover a cave that had not been assessed for more than 40 years. This large cave is locally known as “La Fábrica” and hosts a big mixed colony of Lesser-long nosed bats and the insectivorous Macrotus waterhousii.

The field trip to the Pinacate volcano was a great success and we captured and sampled more than 90 animals. As females are in May either pregnant or lactating, we focused on working with females who were not pregnant to reduce the impact on the animals. This was already the second year for the Pinacate sampling, and my upcoming third and last visit in May 2017 will conclude the field work.

In November/December 2016, we visited again the Chamela-Cuixmala site. This time everything worked flawlessly and we captured bats over 15 nights on Don Panchito Island. We caught a total of 126 animals and collected samples from all individuals. Originally we had planned another visit to Callejones, but we had to cancel that part due to security concerns in the area.

At the moment, I am processing the samples collected during the past year. In March 2017, I analyzed the already available pollen samples and right now I am starting with processing of the microbiome samples.

Financial Report:

The fund provided for this project by the Elisabeth-Kalko-Foundation were essential for the success of the activities described above. Attach to this report I include all the tickets and bills from the field trips in PDF format. The difference between the amount awarded to me from the Elisabeth Kalko Stiftung (4400 EUR) and the actual expenses (6026 EUR) was covered by another grant awarded by the Rufford Small Grant Foundation (grant number 18771-1; Awarded in April 2016).

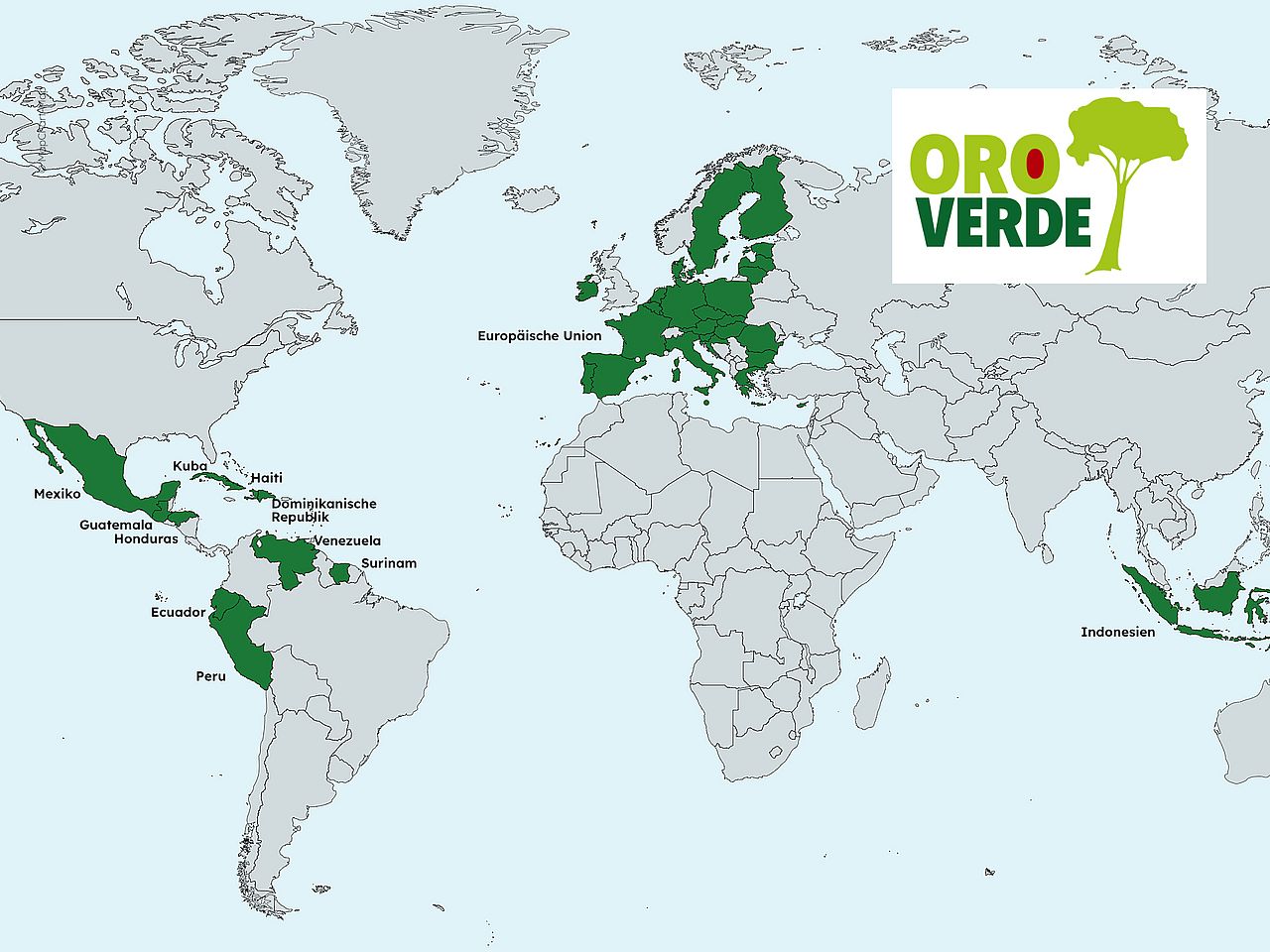

Entdecken Sie jetzt die Welt von OroVerde

Wie sehen Regenwälder aus? Warum werden sie zerstört? Und wie können wir sie schützen?

Wie können wir einkaufen und dabei Regenwald schützen? Was können wir sonst tagtäglich tun?

Erfahren Sie mehr über unsere Projekte: Regenwaldschutz und Entwicklungszusammenarbeit gehen Hand in Hand.

Sie haben Fragen? Wir helfen Ihnen gerne weiter!

OroVerde - Die Tropenwaldstiftung

Telefon: 0228 24290-0

info[at]oroverde[dot]de

Fotonachweis: Luis Roberto Viquez-Rodrigues (Alle)